Do you know the strategy of the bank or credit union that you work for?

a) Yes

b) No

c) This is a trick question, right?

If you chose a), congratulations! Self-deception regarding life’s realities is a great coping strategy. You won’t go far in life, but it won’t matter because you’ll convince yourself that you did.

If you answered b), don’t feel bad. You’re not alone, and it’s really not your fault that you don’t know your firm’s strategy. I’ll explain that further in a minute or so.

If you picked c), you’re a true gonzo banker, and I share your pain.

***

A blurb on Harvard Business Review’s website reported the following:

Employees don’t know your strategy

Surveys suggest that 50 percent of employees don’t have a clear understanding of their company’s strategy. What’s worse, that lack of knowledge is even more pronounced for sales and service employees. Frank Cespedes’ article for ThinkSales “outlines the issues and explains why withholding information about strategy for competitive reasons often results in greater risk for the business.”

If we suspend rational belief for a moment–an easy task for those of you who chose a) above–and take the purported results of these surveys as representative of the banking industry, then it raises an important question:

Why do 50% of employees NOT have a clear understanding of their company’s strategy?

***

The HBR blurb implies that employees don’t have a clear understanding of their firm’s strategy because their company intentionally withholds information from employees in fear that competitors will get wind of it. I don’t doubt that there are many execs who want to keep their firm’s strategy a secret from their competition.

But I would argue that there is another, and much more prevalent, reason why half of employees don’t have a clear understanding of their company’s strategy:

The company doesn’t have a clear strategy.

***

When asked what their firm’s strategy is, there is no shortage of bank and credit union execs who say, “our service.” Sometimes they even throw the word “superior” in there.

Does that mean: “We fix our mistakes better and faster than the other guy!”? Or “We have friendlier people than they do!”? Can they quantify this alleged service superiority? Oh wait! I know! They mean they’re more “convenient” than other banks. Uh huh.

In reality, the default strategy for many banks and credit unions is: “We’re not them.” Where “them” are the mega-banks that the CFPB (Civil servants Fixed on Punishing Banks) would have us believe are evil.

Many people believe that Peter Drucker said it best when he said, “Strategy is as much about figuring out what you won’t do, as it is about what you will do.” Few people, however, seem to like my corollary: “If you don’t figure out what you won’t do, you’ll find yourself in a lot of doo doo.”

I bet those 50% of employees who don’t have a clear understanding of their firm’s strategy have no clue what their firm won’t do.

***

I remember an incident a few years back (OK, a lotta years back) when I was a junior IT strategy consultant. The project team and I came back to the home office after interviewing execs and collecting data. The partner in charge asked the team, “So…what’s their IT strategy?” And we unanimously said, “They don’t have one.”

The partner nearly exploded, “Of course they have an IT strategy! It might suck, it might be poorly formulated, it might be poorly communicated, but damn it, they have an IT strategy! It was your job to figure out what it is!”

***

It’s not an employee’s job to figure out the firm’s strategy. Unless, of course, that employee is the CEO. The CEO’s job is to figure out what the strategy is, figure out if it’s the right strategy, and if it isn’t, to correct it and develop a new one, then communicate it, and execute on it. Actually, that’s just one of the CEO’s jobs. What a sucky job that is, eh?

Did you catch all the pieces? Let’s go through them again:

To appease the Harvard dude, we can modify #4 to read “How do we communicate the new strategy…without letting our competitors know what we’re doing?” I think his contention, however, is that this isn’t an important addition in the scheme of things. And I agree.

***

There is something else that bugs me about the HBR blurb. To refresh your memory (and save you from having to scroll back up), it said:

“What’s worse, that lack of knowledge (of the firm’s strategy) is even more pronounced for sales and service employees.”

This is a serious misinterpretation of the data.

The problem isn’t that sales and service employees don’t know their firms’ strategy. The problem is that they feel the pain of a poorly defined strategy more so than bean-counters sitting in headquarters.

It’s the sales and service folks who have to tell customers “no” because their bosses tell them to, because their incentives are structured in such a way that they personally profit by not giving customers what they want, or because their company has inferior products or services for a particular client or prospect. And, in the back of their minds, while telling the customer “no,” they hear that little voice reminding them what their company’s alleged strategy is. What a sucky job they have, eh?

***

So here we are at a certain point in time.

But at some previous point in time–namely, that point in time when the last strategy formulation effort took place–it’s a good bet the then-current strategy wasn’t defined and adequately assessed. And after the then-new strategy was formulated, it’s a good bet that the then-new strategy wasn’t clearly communicated, nor has it been perfectly executed.

And so the sins of the past hurt efforts to determine the strategy of the future, because few firms take the time, and expend the effort, to clarify their current strategy, assess it, and figure out if it was design or execution that is causing the under-delivery of promised results.

As a result, the senior exec team may think it knows what the company’s strategy is, but in reality, it isn’t what the plan created last year–or two or three years ago– says it is.

This leaves many companies in what can best be described as a

STRATEGY FOG: A state of being in which an organization is unable to clearly see where it is, how it got there, where it’s going, and/or where it should go.

***

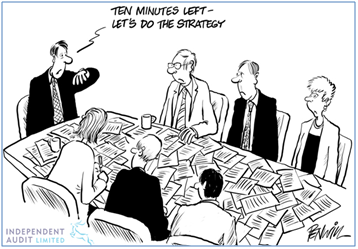

As we look ahead a few short months to the start of the 2016 planning season, many firms–namely those who don’t read this post–will once again repeat the sins of the past, and ignore steps #1 and #2 (and, to a large extent, #4) of the five easy pieces to strategy.

With better clarity regarding the current strategy–and an understanding of why (and to what extent) it is and isn’t working–developing and communicating a new strategy (and how it will be different) becomes a helluva lot easier.

But that still leaves an important question unanswered: How well will the firm execute on the new strategy?

If your organization wasn’t particularly good at executing on the previously-defined strategy, what kind of wacky weed are you smoking that makes you think the company will be good at executing on the new strategy? If you don’t do an honest assessment of capabilities–in the context of the firm’s strategy–you cannot answer the question I just posed.

Bottom line: Strategy formulation is a contextual exercise. That is, it happens within the context of a firm’s current strategy. Without clarity of the current strategy, future strategy development is bound to be flawed. Without this clarity, you may be stuck in a Strategy Fog.

Ron:

This may be the best article to ever appear on the GB. May I use this with attribution?

Thanks,

JPL

JPL:

Thanks for the kind words. Use it anyway you want.

“Let the words be yours, I’m done with mine.”

–Jerry Garcia

RS

I’ve found that strategy involves defining “where” and “how” the company will compete. “Where” includes market segments, geography, business lines/products. “How” includes value proposition (answering the consumer’s question, “why should I do business with you”), channels, core capabilities. As you correctly observe, this also involves being sufficiently specific and focused – strategy can’t be everywhere and anyway.

No argument, Dave. But I will say that, in my experience, the tradeoffs (and required allocation of resources) between segments/geographies/biz lines/products often are not well identified and/or dealt with.

Ron

Good article. The fundamental problem I see is most bankers see strategy as a long-term plan with numbers and action steps.

Charles Revson, the founder of Revlon beauty products, said it best when he said, “In our factories we make cosmetics, at the counter we sell hope.” The tendency is to think product or service, not the essence of what we sell, the real reason people use our services or products.

Craig: Thanks for commenting. I would tend to agree with your assessment of the fundamental problem.

And I wouldn’t disagree that banks should be selling the essence of the products/services. But, I would say that there are banks that attempt to do it, and–in my view–fail miserably at it.

In my neck of the woods (here in the Boston area), one of the 5 largest banks has a strong presence and runs no shortage of TV ads. These ads tend to focus on “achieving your dreams”–i.e., the essence, not the product.

But how ridiculous a claim is it that some checking account is going to help me achieve my dreams? Even getting a mortgage that helps me get my dream house isn’t so much about what the bank does or did, as much as it is MY ability to afford the mortgage?

Even the banks that sell “convenience” as the essence of their product/service tend to overstate the importance of what they offer.

In the end, these efforts tend to be just advertising positioning statements, not strategies.

Ron