ATMs have changed a bit in the last few years. The latest models resemble something one might see on the floor of a casino rather than the clunker model in the corner. Banks whose fleets resemble more of the latter are probably past due for an upgrade.

With the increased usage of debit and credit cards, the rise of eCommerce, and the push for mobile payments, cash has undoubtedly been in decline. However, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco’s 2022 Diary of Consumer Payment Choice found that 20% of all payments were conducted using cash. That’s simply too large a segment to be ignored.

We understand how many financial institutions hard at work on their digital transformation strategies have pushed the ATM channel to the back burner. Maybe it’s time to let ATMs be someone else’s problem.

At its core, an ATM-as-a-service (or “outsourcing”) model looks to consolidate the vendors within the channel and manage the implementation, software, marketing, transaction processing, and day-to-day servicing of a bank’s ATMs, with the goal of allocating resources to other areas. It’s not uncommon for a bank to have two to three different vendors for maintenance, with an additional two to three for cash-in-transit. And with all of the new mergers over the last couple of years, vendor fragmentation is almost guaranteed. The as-a-service model gives banks just one vendor to manage and one invoice for the entire channel.

Plus, ATM-as-a-service provides banks with a unique opportunity to modernize their entire fleet, without the upfront capital costs, through a monthly, bundled flat fee (not to be confused as leasing the machines). In this scenario, the vendor would own the machines and be fully responsible for them while still branding them to the bank.

By moving from the traditional CAPEX model of replacing the machines to an OPEX model where the vendor will be handling the upgrades, banks can:

This isn’t an all or nothing endeavor. Rather, it should be viewed as a spectrum, dependent on how much ownership and control of the channel the organization wants to keep.

With this model, banks are giving up a micro level of control over the entire channel. It’s typical for an institution to have one employee or a department that owns the channel and has an intricate web of processes for managing the vendors, cash forecasting, and service issues that arise on a daily basis. Moving these responsibilities to the vendor can significantly reduce the menial tasks that can be commonplace with in-house ATM management while mitigating the risk of the channel falling into disarray if the institution loses a key employee.

While the bank gives up day-to-day management responsibilities, it maintains complete control of channel strategy, decision making, and marketing. The bank picks and chooses where new ATMs should be located or whether existing ATMs should be moved to more strategic locations. It also presents an opportunity for banks to expand their ITM capabilities, enabling them to better meet customer needs outside the branch.

Ultimately, this allows the institution to become more agile in its decision making while minimizing the risk of deployment costs. Of course, as a bonus, the new ATMaaS vendor can also offer advisory services to help with decision making and strategic needs.

Is ATMaaS going to solve all of a bank’s problems? Are service techs going to show up as soon as there is an issue with an ATM? Will cash deliveries be on time, efficient, and not leave the ATMs out of balance? In the words of Beyond Belief host Jonathan Frakes: “No way,” “Not a chance,” “Not this time,” “Complete fiction.”

The fact is, the vendors offering ATMaaS are the same vendors the bank uses today. Quality of service isn’t going to miraculously change with a transition from a managed service to ATMaaS. An institution may receive some preferential treatment due to its commitment to the vendor, but that isn’t going to change the fact that a labor shortage exists, and these vendors are experiencing high levels of turnover. It’s best to set realistic expectations and not drink too much Kool-Aid during some of these ATMaaS sales presentations.

The “Big 3” (NCR, Diebold, and Hyosung) will compare the total cost of ownership of a bank’s fleet to their ATMaaS offering, and their proposals will be filled with large numbers showing how much it would cost the bank to handle a hardware refresh and manage each service within the channel on its own. This will be followed by an offer of a large discount. But while the discount is real, the numbers may not be, and it’s important for bankers to understand the baseline of the discount and ensure that the hardware and services costs align with the market.

In Cornerstone Advisors’ consulting practice, we’ve seen too many ATMaaS proposals with overly inflated baselines and “discounted” costs that leave banks paying more than peers as reflected in our Contract Vault data.

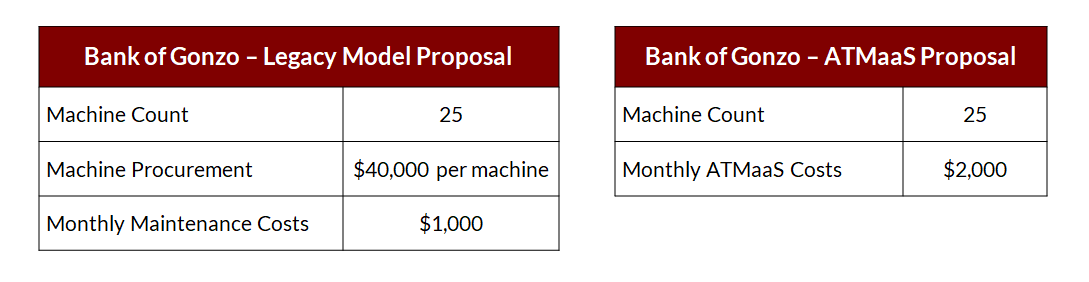

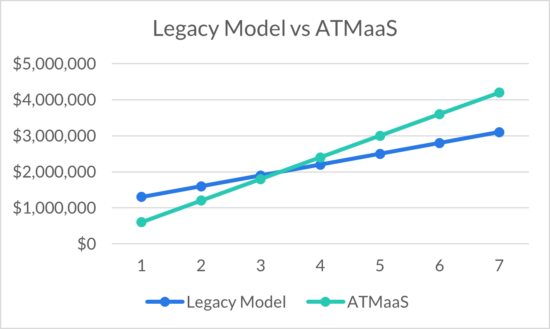

Below is a simplified example of a standard legacy model proposal compared to that of an ATMaaS proposal for the fictional Bank of Gonzo.

At first glance, ATMaaS is more expensive over seven years, with a delta of $1.1 million. However, it is important to look at comparable products here. The legacy model will only include the machine purchase price, and first and second line maintenance of those machines. The ATMaaS model will include machines and maintenance as well as handling cash-in-transit, transaction processing, cash management and forecasting, back office operations, software licensing, monitoring, and security.

The key here is to view the channel as a whole, rather than on an individual contract basis. When the bank factors in each of these areas, as well as its decrease in capital expenses, the delta between the two models can quickly disappear.

This model isn’t for everyone, though. A smaller bank with just five ATMs can easily handle the channel in house. On the other hand, a large financial institution with 1,000+ ATMs requires a dedicated department with the systems and data capable of handling the fleet. In these cases, the increased cost of ATMaaS might not make sense. But for many community institutions that fall somewhere in between, an ATMaaS approach can alleviate the FTE demands of an often laborious and burdensome channel.

The ROI for the bank isn’t going to be found in the hardware or services offered. Rather, it’s going to be in the ability to reallocate human, capital, and technological resources to more critical business areas.

It’s important that banks don’t stop short and ignore the ATM channel just because it has a physical footprint. ATMs and ITMs should be considered more of a “bank in a box” with integration into the digital ecosystem than a siloed channel with minimal functionality. Banks now have the ability to replace drive-thru lanes with ITMs instead of tubes. Customers can prepare ATM transactions on their phones, make loan payments, and even buy/sell cryptocurrency at the ATM. The channel isn’t going to sit and wait for cash to die, and neither should financial institutions.

Whether or not they use ATMaaS to reach their digital transformation end-goal, it’s imperative that banks keep the effort going. This model may help them get there sooner.