“The basic economic resource – the means of production – is no longer capital, nor natural resources, nor labor. It is and will be knowledge.” –Peter Drucker

One of the most fundamental strategic issues facing banks today is the ability to grow commercial loans in the midst of a rapidly changing U.S. economy. There is a big, fat elephant in the banker’s living room that I would like to reveal: most banks have lost their focus on true C&I lending growth and have replaced it with a voracious love for commercial real estate. If bankers cannot find the strategic stomach to reverse this course, they will be relinquishing one of their prime sources of future franchise value – the trust and partnership of the business owner.

Alarmist? Let’s take a quick look at the numbers. The chart below plots the growth of commercial “C&I” loans vs. commercial real estate/construction loans (“CRE”) over the past 10 years. Industry-wide, C&I loans have grown at a slow, 5% annual rate, while commercial real estate has grown at twice that pace. Banks now hold 50% more loans in commercial real estate than they do in non-real-estate-secured commercial loans.

This CRE buildup has been even more pronounced in the mid-size bank segment, where banks $1 billion – $10 billion have seen no C&I growth over the past 10 years while growing CRE at a brisk 9.4% annual rate. CRE is now more than twice the exposure of C&I at mid-size banks.

Clearly, the regulatory community has voiced concern about this buildup, and bankers are preparing for much tougher portfolio examinations and limits on CRE exposures in the future. In fairness, many bankers are now saying, “It’s time to shift our mix more toward the C&I side of things.” But here’s the problem: as our country shifts more to a knowledge-based, technology-driven economy, the opportunities for traditional C&I loan growth will become harder and harder to find. Over the past 10 years, the amount of outstanding bank C&I loans relative to the size of our economy (nominal GDP) has decreased from 9.6% to 8.2%. If C&I loans had kept pace with the overall economy, bank portfolios would be 17% larger than they are today!

Clearly, the regulatory community has voiced concern about this buildup, and bankers are preparing for much tougher portfolio examinations and limits on CRE exposures in the future. In fairness, many bankers are now saying, “It’s time to shift our mix more toward the C&I side of things.” But here’s the problem: as our country shifts more to a knowledge-based, technology-driven economy, the opportunities for traditional C&I loan growth will become harder and harder to find. Over the past 10 years, the amount of outstanding bank C&I loans relative to the size of our economy (nominal GDP) has decreased from 9.6% to 8.2%. If C&I loans had kept pace with the overall economy, bank portfolios would be 17% larger than they are today!

There are four major reasons for the headwinds in C&I loan growth:

Reason #1: The transition from a manufacturing to a service and knowledge-based economy.

As more manufacturing goes to suppliers overseas, U.S. businesses require less short- and long-term working capital than the former capital intensive industries. Three quarters of the work force in America is now associated with the service economy. In addition, the rise of knowledge-based companies also makes traditional bank financing rules quite whacky. Let’s take a quick look at new-economy player Microsoft:

Microsoft’s billions of annual earnings are generated almost 100% by knowledge assets and do not require heavy financing to grow. But it’s not just tech companies. Starbucks may own a good chunk of real estate, but a huge amount of its value is locked up in its “brand equity”:

As even more small and mid-size businesses become knowledge intensive, many bankers will struggle with how to handle these relationships.

Reason #2: Improvements in the supply chain are dropping inventory requirements and capital outlays.

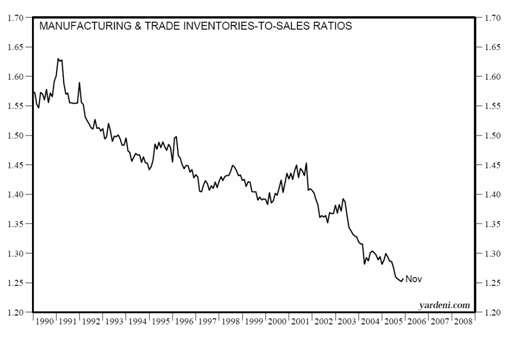

One of the most interesting economic statistics to watch is the decline in the inventory-to-sales ratio in the United States in the past 15 years. As the chart below shows, this ratio has dropped a full 20% because of more efficient business supply chains. Real-time information has allowed companies to optimize their inventory levels. In addition, as businesses replace older, more expensive equipment with automation that streamlines the supply chain, the intensity of capital investment actually declines, leaving less in long-term assets to be financed by banks.

Reason #3: Improvements in the “cash conversion cycle” are improving working capital and reducing needs for financing.

According to CS First Boston, the time it takes businesses to turn goods paid for into cash dropped by 30% during the 1990s, from more than 100 days to 71 days. Just consider the poster child of tight cash conversion: Dell Computers. Due to astute structuring of its operations, Dell only assembles a computer after a customer has paid in advance with a credit card, and then Dell pays its suppliers on common 30+ day trade credit terms – meaning Dell operates with negative working capital requirements. No need for a bank loan there! Wal-Mart also sells the majority of its inventory before payment is due. With the continued rise of electronic business-to-business activity, the amount of “accounts receivable” financing will continue to decline for most businesses.

Reason #4: Specialty finance companies are eating away at bank commercial share.

Banks are very proud of the risks they are not willing to take on business lending, but that hasn’t stopped other competitors from moving in to seize riskier but higher yielding deals. GE Commercial Finance now boasts an amazing $230 billion in commercial assets, more than the C&I portfolios of Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase combined. While many banks have had fits and starts and some disasters with specialty finance, there’s no denying that commercial finance, leasing and commercial brokerage companies provide stiff new competition for business asset generation.

What’s a Poor Banker to Do?

In this new environment, much of what we all learned in Commercial Banking 101 needs to be challenged and new creative strategies need to be employed to compete in the new world of business banking. While there are no easy answers to this quandary, there are a few strategic mandates I would like to offer:

Services must broaden beyond credit – with diminished need for traditional financing, banks must find additional ways to add value beyond lending. Treasury management services must continue to be beefed up. In fact, banks may need to reach back even deeper into the supply chains of their own customers to see where they can add value. Should they archive business documents? Should they be an accounts payable and collections outsourcer? Should they integrate their Treasury management offerings with financial applications delivered in an ASP environment? It’s time for banks to look harder at the strategic role they can play for businesses. I credit folks like Amegy Bank in Texas for making Treasury Management services a centerpiece of their commercial banking offerings.

Industry knowledge must deepen – the only way for bankers to be a true business partner will be to clearly understand the industry they are serving. One of the key facets of GE Financial’s success has been the deep, dirty-fingernail knowledge that this company brings to its financing operations. In fact, GE actually has provided consulting advice in areas like supply chain management and Six Sigma for its finance clients. How many banks have this type of institutional knowledge and capability?

Underwriting must become more strategic – the good ol’ days of simply advancing a percentage of receivables, inventory and equipment are fading fast. In order to compete in the future, bankers will need the capabilities to evaluate “softer” assets in a company like intellectual property and intangible assets like brand equity. Bankers will need to analyze more than the financials – they will have to understand how their clients are positioned strategically in their own industries.

The bank must become the network – in terms of future strategic positioning, commercial bankers have to think of themselves as much more than financiers of business. As the business world becomes more information intensive and the supply chains of all companies start to intertwine, banks must position themselves at the center of this network. I have long admired Silicon Valley Bank in California for positioning itself as the “partner who is connected to all the right people in the technology, life science, private equity and premium wine industries, but who employs all the right people to serve these markets.” With deep industry knowledge and a huge network of resources, Silicon Valley does more than just finance, it “connects” businesses up with the people, information and knowledge they need to compete. In the future, commercial banks will need to look beyond traditional commercial services and think about things like M&A/investment banking, hooking up clients with “angel” investors, helping to link up clients with experts and board members, and even providing industry information and advisory services. Banks who specialize along certain industries will be able to amass valuable financial and strategic data about companies that can be aggregated into powerful benchmarking information for clients – this is adding value in more ways than just providing money. Sure, banks have tried and failed at many of the more exotic commercial offerings in the past, but I’m confident the second and third tries at this more strategic approach to business banking will be wildly successful.

The Business Banking Franchise

As we move into 2006, bankers everywhere need to look in the mirror and think hard about “Just Saying No” to more and more commercial real estate. Sure, a quick set of loan-to-value and debt-service coverage calculations are simple in a market where real estate values have been rising. Who wouldn’t get a little intoxicated with the volume and want to eagerly move on to the next hot deal. However, this deal-making alone won’t make our industry an active player in the emerging knowledge-based economy. It’s time to get started on the tougher strategic work at hand.

-spw